Consultant Clinical Psychologist and Aware’s Clinical Director Dr Claire Hayes recommends a three-step approach which she has developed to explain the core principles of cognitive behavioural therapy to medical practitioners and their patients, and help them to understand and manage anxiety

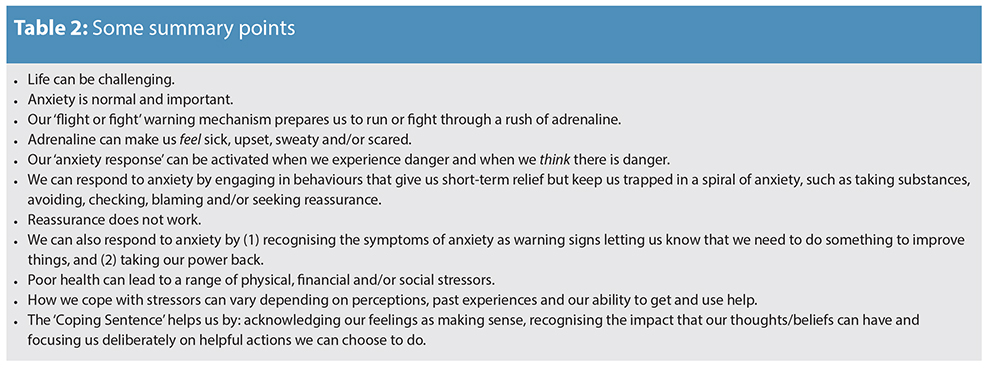

You may have noticed that the number of your patients who experience anxiety has spiralled in the last few years. If so, you will probably know that reassurance, although nice to get, does not work. Its benefits last only as long as it takes someone to think, ‘Yes, but she seems very young. What would she really know?’, or ‘Hmmm, he looks as if he is about to retire. Maybe he is not as up-to-date as he should be’. The range of such thoughts is probably infinite but the ones which can quickly escalate anxiety are the ‘What if?’ thoughts. ‘What if I am really sick?’, ‘What if I don’t get better?’, ‘What if I die?’ ‘What if the person I love is really sick?’, ‘What if he doesn’t get better?’, and ‘What if she dies?’

The old saying, “Doctors differ and patients die” may be true, but this is not helpful when someone uses it to actively discount all of the sensible reassurance you have just patiently given.

Triggers of anxiety

Triggers of anxiety can range from worrying thoughts regarding climate change and the environment to specific health concerns for individuals and or for their family members and friends. We know that anxiety can literally cause ‘dis-ease’. Its physiological components can increase rapidly, even to the point when someone thinks that they are going to faint or even die. It can feel sickening and frightening and our natural instinct is to do anything to feel better. We may learn to manage anxiety through avoidance.

We may seek reassurance or we may do something else that gives immediate relief such as taking caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, sugar or some other substance. We may also slip into repetitive behaviour such as rechecking doors or rewashing our hands over and over. While we can get immediate relief from these actions, it tends to be short-term. All that has to happen for any of us to feel anxious again is to see, hear or think of any of our anxiety triggers. Also, substances such as caffeine, sugar, alcohol and drugs can increase anxiety rather than reducing it. Anxiety can be triggered by real fears as well as by thoughts. Some patients could be seriously ill and for some, the inevitability of their death is sooner, rather than later. Thoughts such as ‘What if I get worse?’, ‘What if I don’t get better?’ and ‘What if I die?’ are understandable. If these lead to focused conversations on how to make the most of the time the patients have right now, they could be helpful, difficult as that might be.

Facing anxiety

Paradoxically, facing anxiety can make people feel worse in the short-term. Why would any of us deliberately do something that we know is going to make us feel anxious, whether that is walking away from a door that we think we have left unlocked, say ‘No’ to the substance that we know gives us immediate relief or face the reality that the time we have left on this earth really is short? Checking a door over and over may seem irrational behaviour to some, but if it makes people feel better, then they will keep doing it.

Diagnosing anxiety disorder

The Diagnostic Statistical Manual (DSM), which is now in its fifth edition and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), which is in its 11th revision, classify anxiety disorders. It can be very helpful to know that certain behaviour such as checking is a normal part of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and avoiding places, people and/or transport can be a normal part of social anxiety, agoraphobia or panic disorder.

Diagnosing someone as having an anxiety disorder can backfire. My experience of working with people of all ages who have anxiety has taught me that they have common characteristics. They tend to be high achievers, do not like making a mistake, minimise what they do well and worry about what they think they will not be able to do.

A diagnosis of an ‘anxiety disorder’ can become yet another reason to blame themselves for not being ‘perfect’.

If the diagnosis does not lead to an understanding of anxiety and helpful actions to manage it, the labels can become excuses to continue engaging in the same behaviour. Lack of helpful action can lead to “learned helplessness” which as Prof Martin Seligman highlighted, can lead to depression.

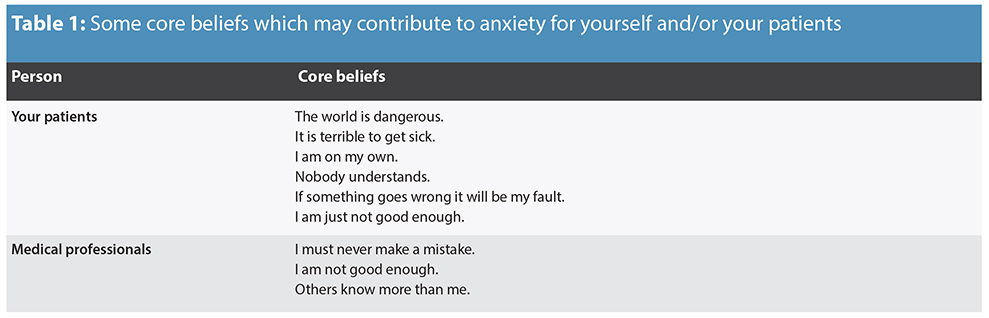

Some core beliefs

It can be much more helpful to see anxiety not in terms of an “illness”, but instead as a normal reaction to real and/or perceived danger. Just as our smoke alarms can become faulty and respond to stimuli such as wind as well as smoke, our “anxiety alarm” can respond to our thoughts, our beliefs and our actions. We first acquire core beliefs when we are young children. They tend to be “black and white” and as we get older we may not realise that they are quietly operating in the background. Some core beliefs you and/or your patients may have are contained in Table 1.

The ‘Coping Triangle’

The ‘Coping Triangle’

So how can you help yourself and your patients to understand and manage anxiety? I suggest using a three-step approach which I have developed to explain the core principles of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). This is called the ‘Coping Triangle’.

Step One is to catch thoughts, feelings and actions in relation to something that is causing stress.

Step Two is to ask the following four questions:

- Do the feelings make sense?

- Are the thoughts helpful or unhelpful?

- What beliefs are underpinning this?

- Are the actions helpful or unhelpful?’

Step Three is to use the ‘Coping Sentence’: ‘I feel … because … (‘I think) … ‘ but …’

Finding Hope in the Age of Anxiety (Hayes, 2017), How to Cope. The Welcoming Approach (Hayes, 2015) and The Professional’s Guide to Understanding Stress and Depression (Hayes, 2016) contain many examples of how to use the three steps of the ‘Coping Triangle’.

The ‘Professional’s Guide’ is a booklet written in collaboration with Aware and the Institute of Chartered Accountants, and is free to download. The third step, the ‘Coping Sentence’ can be an important and effective tool in helping yourself as well as your patients to acknowledge feelings, see these as making sense due to thoughts, beliefs and/or actions and focus on powerful choices to help manage anxiety.

‘Treatment is a paradox’

‘Treatment is a paradox’

My experience of anxiety is that the treatment is a paradox. Overcoming it can make people feel worse initially rather than better; recognising that certain actions such as checking, avoiding, repeatedly seeking reassurance and/or relying on substances are unhelpful, but can be very freeing.

Once we understand that our experiences of anxiety are logical based on our thoughts, beliefs, actions and/or circumstances and that overcoming anxiety can make us feel even more anxious initially, we are able to deliberately face whatever it is that triggers anxiety.

You may have found that once ‘the worst’ arrives, the patients who were most anxious, cope well. Somehow once their worst fears are realised, they no longer have to worry about them happening. Instead, they take a deep breath and face them.

Taking a few deep breaths is one of the most helpful actions we can do to help us manage anxiety. A simple exercise is to tighten our non-dominant hand, while at the same time breathing in. Then hold our hand for the count of three while thinking a helpful thought such as ‘I choose to breathe slowly’ and then relax our hand while breathing out.

Dr Gary O’Reilly has developed an excellent app called ‘Mindful GNATS’. This is free to download and is an important resource to help people learn effective relaxation techniques.

Other helpful thoughts can be incorporated into the ‘Coping Sentence’ such as: ‘I feel anxious because I think… but I choose to… act in a helpful way/do the best I can/worry about it if or when it happens/get and use support/face my fears head on/recognise and appreciate what I do well/make the very most of the time I have.

Given that reassurance does not work, how might you use the ‘Coping Sentence’ to help your patients when they say to you ‘But what if I am really sick?’ ‘What if I don’t get better?’, ‘What if I die?’, ‘What if the person I love is really sick?’, ‘What if he doesn’t get better?’, and ‘What if she dies?’

Coping in reverse

You can use an adaptation of the ‘Coping Sentence’ in reverse by acknowledging how you think the person is feeling, link that with what you think they might be thinking and/or what their circumstances are and focus on helpful actions they might take.

For example: ‘I think that you are feeling anxious because you think that you could be really sick so let’s focus on what helpful actions you can take right now’ or ‘I think that you are feeling anxious because you think that … could be really sick so let’s focus on what helpful actions you can both take right now.’ ![]()

References

References

- Hayes, C. (2017). Finding Hope in the Age of Anxiety. Dublin: Gill.

- Hayes, C. (2017). Finding Hope in the Age of Anxiety. Audio Book: Australia: Bolinda.

- Hayes, C. (2016). The Professional’s Guide to Understanding Stress and Depression. Dublin: Institute of Chartered Accountants. http://www.charteredaccountants.ie/Stress-Guide.

- Hayes, C. (2015). How to Cope. The Welcoming Approach to Life’s Challenges. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

- Hayes, C. (2015). How to Cope. The Welcoming Approach to Life’s Challenges. Audio Book: Australia: Bolinda.